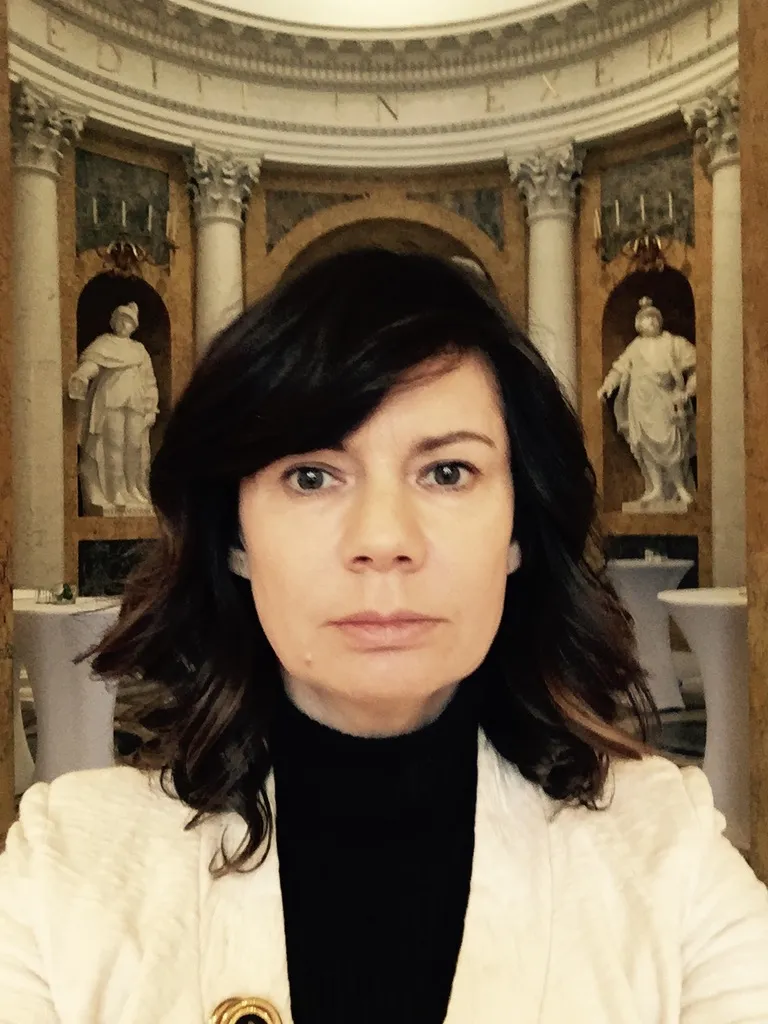

From the corporate jungle to your own backyard

From the corporate jungle to your own backyard

Jump in the deep end

Although in the 1990s everyone dreamed of working in a corporation because it would bring us closer to the desired West, my first challenge had little to do with it.

From an early age, I jumped in at the deep end. The first major challenge in my life was to take on the farm of a close family member.

My aunt became seriously ill during the period when I didn't get into my dream university. Someone had to take care of the farm, and as we had no other young people in the family with time to spare, instead of going into English, I took on crop management - four hectares of blackcurrants and a hectare of strawberries. Not to mention the 10 chickens I had to slaughter by hand - quite a challenge for a city girl. The rooster was fortunately baked, as he managed to escape at a strategic moment.

The farm was in the village of Barnimie. For me it was almost, like, at the end of the world. My aunt lived 4 km outside the village on a colony. The village consisted of maybe one street and a church - there was absolutely nothing to do, and on top of that we didn't have mobile phones back then (can you believe it was also possible to live like that?), so when I needed advice, I would go, and if I did, I would go to the post office in a bigger town about 6 km away - Drawn - to order a call and just call for a while.

After every such trip I was breathless and vowed never again...until the next time. There was no other choice, such were the times, and I couldn't let my aunt down. This was my first real school of life.

Japan - a lesson in life and language

While today it is almost natural for everyone to go to university, 30 years ago, it was not so obvious. A university degree was considered something prestigious and desirable, and getting into a university at a renowned university in the capital was an unusual challenge for a girl from Silesia. And to graduate was to be guaranteed a good job. So I took up Japanese studies, later adding marketing at the Central School of Planning and Statistics (today's Warsaw School of Economics). This also involved another challenge - moving to the big city, Warsaw.

On the one hand, I was looking forward to the new opportunities that life in the capital offered. I could expand my knowledge, make inspiring contacts and benefit from the city's cultural wealth. On the other hand, I was terrified of the new reality. Finding myself in an unfamiliar place, where I know no one and am on my own, caused me great anxiety. However, these mixed feelings - a combination of excitement and fear - became the driving force behind my determination.

After one lecture, a Japanese mentor close to me rightly pointed out that a mastered language is not a qualification in itself, because now at most I can compete with all the Japanese, but without the weapon in my hand in the form of a hard job, it will be hard for me to gain valuable experience.

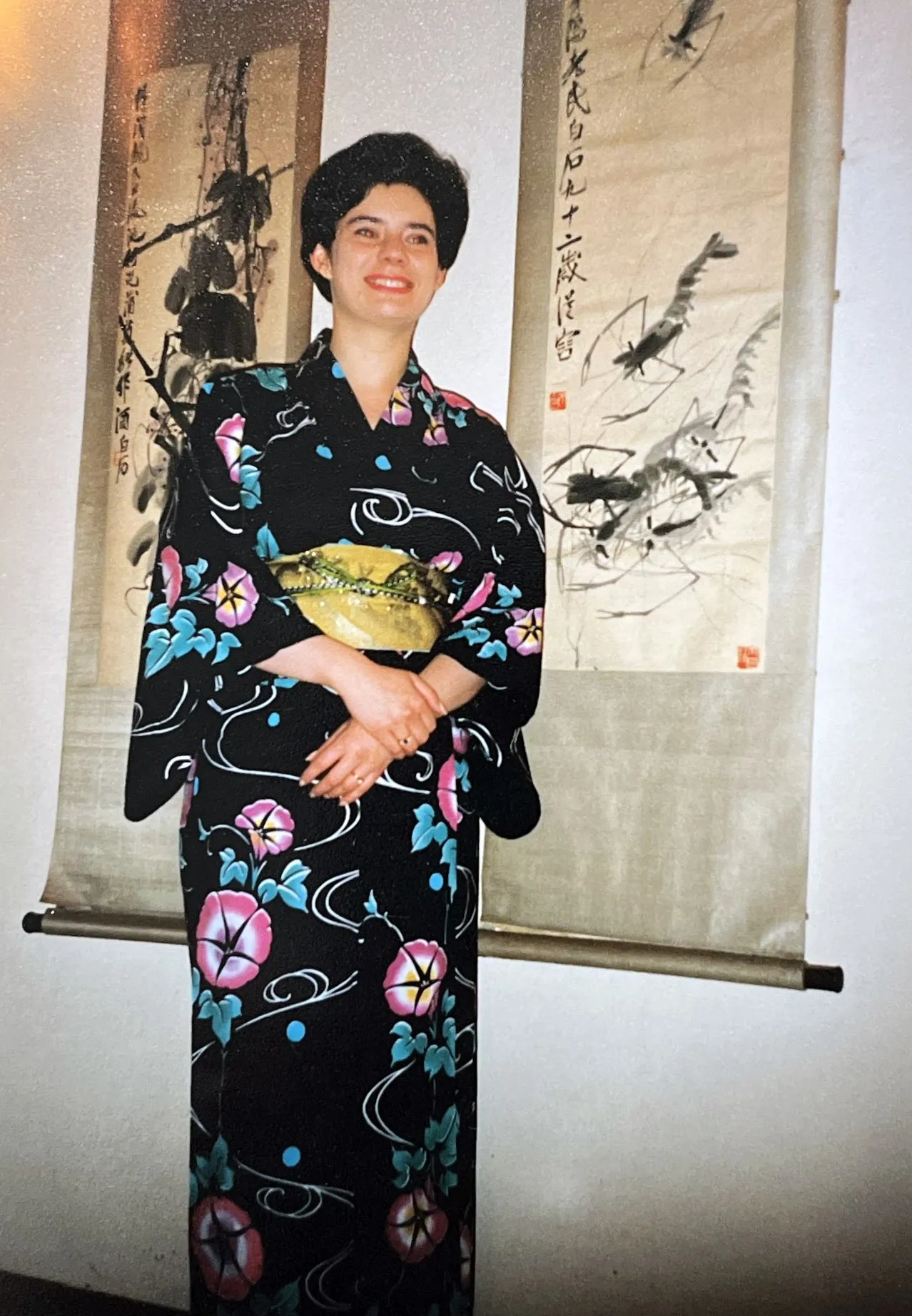

In Warsaw I worked with a group of investors, among them was a woman who had lost her luggage on her way to Poland and my mother lent her clothes. She then invited me to Japan to Kitakyushu. And that is how I found myself in Japan, to which, at the time, the trip cost USD 150 by Aeroflot . The only solution turned out to be to take a job in the Mizushobai system, without papers, where my pay depended on my popularity.

I worked in a restaurant, club and karaoke club and my job was to entertain Japanese people while they feasted so that they would feast for as long as possible and, when ordering more food and drink, leave as many yen as possible in the establishment. For the duration of my work, I took on the role of a Japanese lady.

Before I started working at the restaurant, however, I went through a rite of preparation. This involved not insignificant challenges such as a daily seven-hour appointment with the hair and make-up artist before starting work or dressing in a kimono girded with a 12-metre-long constricting obi belt in which it was impossible to breathe, all in order to be attractive in the eyes of Japanese customers so that I could discuss long nights with them, which translated directly into their time in the restaurant and, in turn, the size of their bill.

If you have ever spent seven hours in a hairdresser's chair from 4am onwards, you can imagine the 'undisguised pleasure' in repeating this process every day for months.

Ultimately, something positive came out of this experience. The Japanese were very interested in the history and political changes in Poland, so long discussions about Walesa or Wajda were not uncommon. By constantly entertaining the customers, I learned fluent Japanese.

I no longer found it difficult to talk about political issues, which many people find complicated even in their mother tongue. Although I didn't use the language very often when I returned to Poland, 20 years after my studies, fluent Japanese proved to be a bargaining chip in negotiations with an extremely important partner of the foundation of which I am the president today......but about that in a moment, because a lot more has happened in the meantime.....

Coca Cola: a marathon in the world of beverages

At Tomasz Wardynski's we privatised Poland I remember once realising that I had already worked 27 hours without sleep. It was a no-holds-barred ride.

BHP? And what is it?

The work ethic, or rather the scarcity of it, was, as it were, the leitmotif of the 1990s. Those times were definitely governed by their own rules. We were privatising Poland, partying until dawn and back to work from the morning. Sometimes we drank whisky and coke all day long.

I still remember one of our great successes, when we mounted an advertisement in the form of a clock with Coca-Cola written on the top floors of the famous Forum Hotel - at that time the most modern skyscraper in Poland. It was to be visible all over Warsaw! And how did we do it? Completely drunk.

You could say that health and safety rules were non-existent. An example was our office on the 26th floor in the Palace of Culture, where the floor below us was locked. This meant that we had a completely cut off escape route. At the time, however, no one thought about it, so it's a miracle that no one got hurt.

Cassettes, cassettes...

The next stage of my path was working at Warner Home Video. It was a nightmare. The videotape market was as dull as oil. Plus, all my boss wanted from me was to drag me to bed. Of course, despite numerous inelegant plays, for which in today's world many a gentleman could be sued, and despite attempts to bribe with promotions, I did not give in. As a result, I was left with no option but to get the hell out of there quickly, because I quickly learned that an offended boss's pride is not your ally.

I later worked for the famous Art-B company, which became a symbol of financial scams in the 1990s. The company became famous for its use of the economic oscillator, which allowed the same payment to earn interest in banks dozens of times. From a small company in Cieszyn, Art-B transformed into a giant holding company, trading in trillions of zlotys and employing thousands of people. The history of this company was so fascinating that Canal+ created a documentary series on it - it was a true economic detective story.

Working at Art-B was an extremely difficult time for me, especially as a single mother with a 10-month-old daughter Susie. Everyday life was really hardcore. I would get up at four in the morning to get Zuzia ready for nursery and myself ready for work. I was often so tired that I forgot whether I had already had my morning coffee. After work, I would return home where the second shift - childcare - was waiting for me. Every day was a race against time and my own fatigue.

This lasted until a salutary phone call asking from the only normal boss I had so far, who had also fled Warner a while before me (although probably for slightly different reasons), if I would become marketing or administration director at PZU Życie.

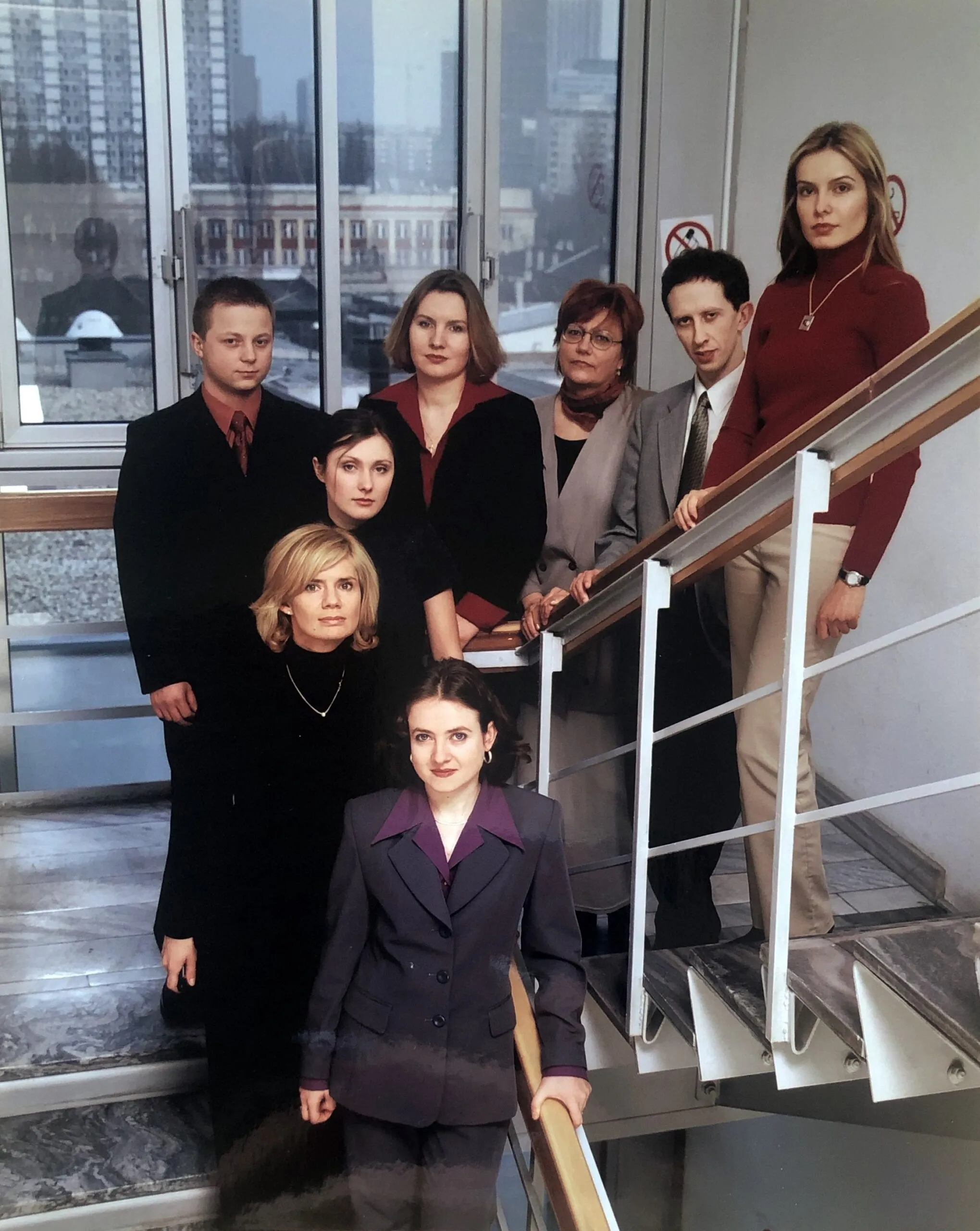

I chose marketing, even though despite 5 years of studies in marketing at SGPiS as life later verified, I knew very little about it. I was given a team of 13 people to coordinate. I was afraid that I wouldn't manage, but I was assigned the support of advisors from McKinsey. It turned out that managing a team is like leading an orchestra - sometimes you have to improvise, but the end result can be really amazing.

One of the crown projects I was responsible for was the well-known pension reform.

'Golden Autumn'. Although professionally it was quite an adventure, we worked non-stop without rest, which translated into health problems soon after.

The story with PZU did not end , as I imagined. After a year of work, the CEO of PZU whispered to me that I should get fired... and eventually he did. I ended up going through the legal route and another 17 years of testifying at the police, the prosecutor's office and in court. I was under permanent stress. I reported to the prosecutor's office for testimony in double underpants and vests, in case they put me in, because I could expect anything. Despite my tragic mental state, I had to move on to find a source of income, so I decided to continue my path in the insurance industry by taking a job at Compensa.

Finance sharks

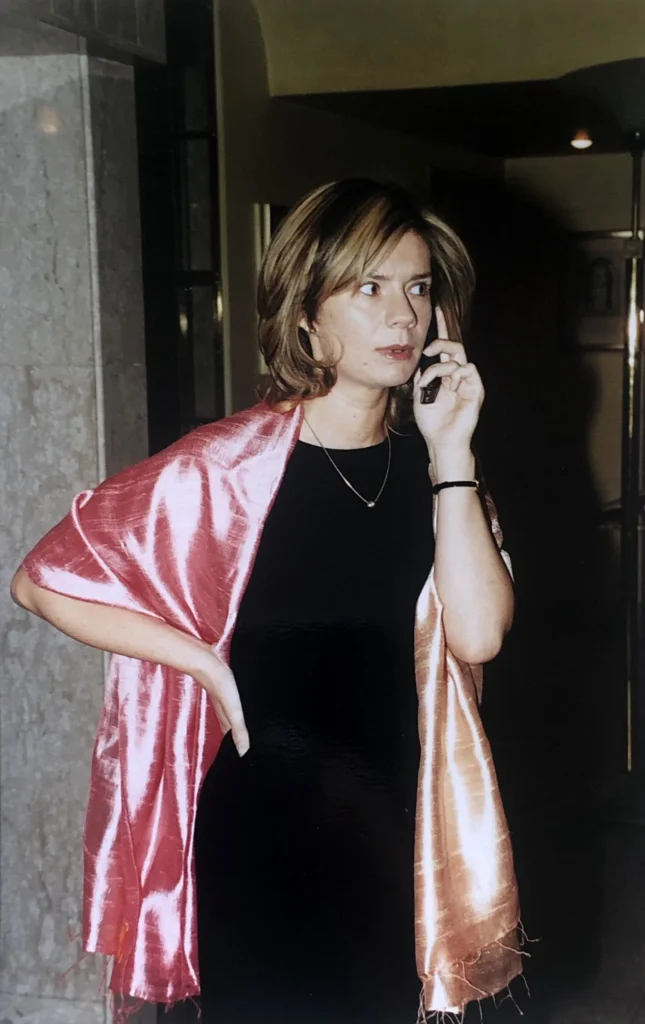

At Compensa I became head of marketing and spokesperson. Organisationally it was a real frenzy as we had as many as four boards Professionally I was in a wonderful frenzy. I wasn't able to reduce the font of the T&Cs yet again to get fewer pages. Those who have scrolled through insurance know what I am talking about.

Later, I worked for a year at the Blue City shopping centre in Warsaw as marketing director. I was supposed to stay longer, but the finance director hated me because I dared to disagree with his nonsensical ideas.

I was from providing creative ideas and he was from sticking to the budget. From his perspective, the two didn't mesh. In those days, it was men who ruled in corporations, so it was obvious who was to be removed from the board.

My professional world was collapsing completely. I was at an impasse, too old for another corporate job with no future and the false hope of a decent retirement. I said to myself, "Enough is enough" and put all the cards on myself.

Own businesses: ups and downs

Together with Era, Siemens Nixdorf, Mebi and a friend, I set up my own business - AITV. We were involved in the complete creation of television, from installing equipment, to creating television programmes, to creating, managing and selling advertising. We were the first and exclusive supplier of television to companies such as McDonald's Poland and Deutsche Bank Poland, among others.

Everything was going well until my partner decided to cheat and steal from me. I had 40% shares, she had 10% and our partners had 50%. The head of McDonald's at the time said that if we were going to operate, it should only be with me, but unfortunately by joining forces, the partner and partners had the majority and decided to get rid of me. Eventually they went bankrupt, but that doesn't change the fact that we lost a substantial half a million, which at the time had a much higher value than today's 500,000.

A tough time, but we persevered as a family and as people.

Royal challenges

Life showed its true face. I was forced to say goodbye to my plans for my own business and return to the structure and hierarchy I knew, because the loan for the flat would not pay for itself and the children (four at the time) would not feed themselves. I took a job at the Royal Lazienki Museum in Warsaw as Marketing Director. I was in charge of practically everything there: from marketing to PR, fundraising, sponsorship and event organisation. I was only supposed to be there for a while, and ended up spending six years there.

Among our distinguished guests were members of royal families from Sweden, the Netherlands, Bhutan, Luxembourg and Qatar. We had many unusual challenges, such as hosting the Princess of Qatar, whose feet could not touch the ground directly, so we had to prepare a special carpet stretching halfway across the Lazienki Park, or Dmitry Medvedev, who travelled with his own lectern so as not to appear too low. I co-organised and initiated the Baroque Opera Festival, the Zone of Silence Festival, the Festival of Light. Over 180 concerts a year. The brand of the Baths has gone from local to global through our activities.

In search of my own path

It was another success story in the corporate world, but I was missing acting on my own terms. I was suffocating in that environment. I was tired of men in their 40s doing whatever they wanted, of their unsavoury and inelegant manners to validate their egos and lack of ethical principles. I was sick of the tyranny and working inhuman hours for 20 years. I was sick of climbing endless rungs of hierarchy. When I was smiling and amicable, I was described as too soft, and when I stood my ground, it was not uncommon for the word 'bitch' to be bandied about behind the scenes.

I was exhausted from constantly proving my worth, ignoring sexist remarks and balancing a work-life that was virtually non-existent.

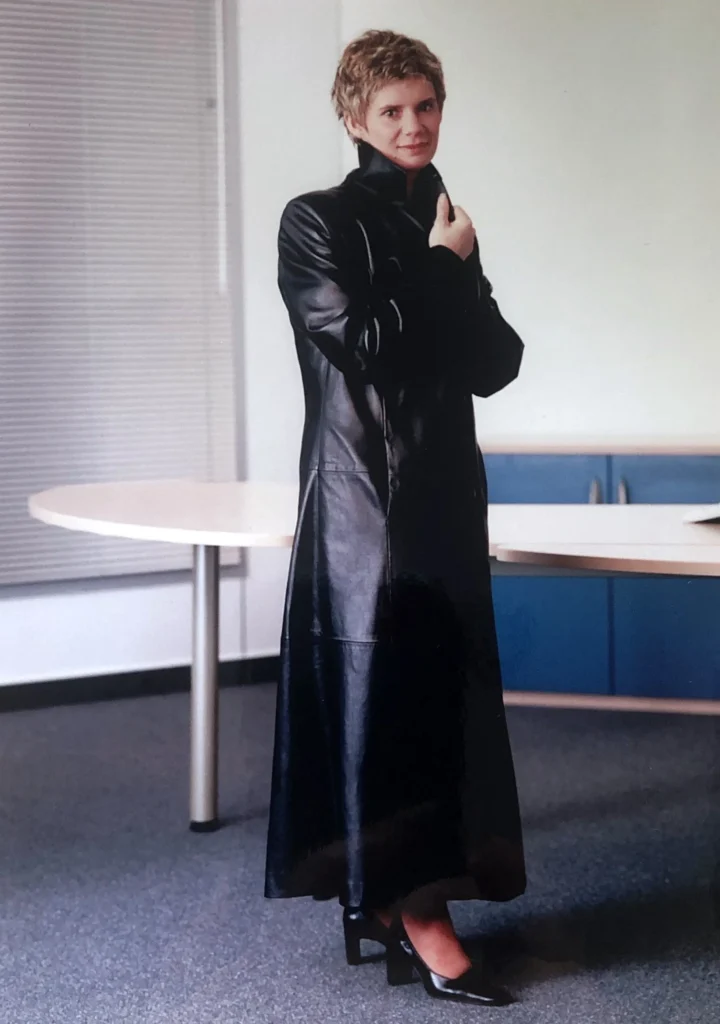

Every day was a struggle with pointless routines and evenings spent trying to regain at least a modicum of normality. I was mentally and physically exhausted, struggling with chronic fatigue, stress and the pressure to always be the best. At some point I realised that I could no longer pretend that it was all worth it. I needed to find a way to take back control of my life and rediscover who I really was, having shed the corporate uniform.

I wanted to finally play by my own rules and, despite my previous failures, I decided to end the phase of working at the Baths and, together with my husband, develop our brands such as VEGESKLEP and PKUSKLEP with healthy food, pharmacies and the florist and real estate business. Now I devote most of my time and energy to the Humanosh Foundation, of which I am co-founder and serve as CEO, which gives me complete life fulfilment. This is where history has come full circle. When, shortly after setting up the Foundation, thanks to my knowledge of Japanese, although no longer as fluent as when we talked for hours about Walesa, we managed to get Japanese donors who were much more willing to speak Japanese than English.

For that matter, the cockerel who was offended by my management of the blueberry field has to this day not been found by anyone.

New horizons

Life can be perverse. That's why I'm here to show you that despite the difficulties, anything is possible. Even in life's most difficult moments, you can fight for a better tomorrow. I would be happy to help you start this transformation today.